It is critical to understand the dynamics of international cooperation in people-centric and just energy transitions.

Vrinda Gupta, Aishwarya Sharma

As the world accelerates its transition to clean energy systems to avert a deepening climate crisis, a critical question emerges: “How to ensure that no one is left behind in the race to net-zero?”

While energy transition is essential to combat climate change, it comes with profound economic and social consequences. In the emission-intensive sectors, particularly across the Global South, communities and workers face the anxiety of scaling down operations, new and advanced technologies and uncertain futures. In the entire process, new jobs and opportunities shall emerge but might not transpire at the same time, place, sector or require the same skill set.

Ensuring that the transition must also be people-friendly, community-centric, and non-disruptive of livelihoods in our current BANI world is paramount. It is important to understand that climate action towards net-zero cannot become another story of global inequity, where the developed world leapfrogs ahead while vulnerable communities pay the price. If this energy transition is to be truly just, it must prioritize communities and should be locally adapted.

This is where global cooperation matters.

Our recent conversations with stakeholders across the globe reveal a stark reality about the ongoing discourse for just energy transitions and the global efforts towards it. Stakeholders share that while energy transitions are happening globally, they are often far from “just”. There exists a disconnect between rhetoric and reality, demanding an urgent attention, especially in the light of Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs) which had lately gained momentum as a key mechanism for international cooperation on this issue.

On the sidelines of COP in Azerbaijan, our CEO Srinivas Krishnaswamy had the opportunity to interact with stakeholders from Indonesia to South Africa to Latin America, particularly global south and here is what we learnt:

Decoding Just Transition

The concept of ‘just transition’ does not have a universal definition and rightly so. As several experts from developed nations emphasise in our interviews, ‘just’ or ‘people centric’ transition must be context-specific, shaped by the unique socio-economic, political, and cultural realities of each country and community. This absence of a fixed definition allows for flexibility in reflecting local aspirations and priorities but also induces complexity.

Over time, just transition thinking has evolved across three critical dimensions:

Conceptual Expansion: Once limited to coal workers, the scope has broadened to include informal workers, women, supply chain actors, local communities and gender considerations. It now spans multiple sectors, including automotive, energy-intensive MSMEs etc and speaks to deeper economic and social transformations.

Policy-Practice Disconnect: While the discourse around just transition has expanded, its implementation remains limited. Policies often invoke inclusive rhetoric like “leave no one behind” without integrating meaningful social protection, community participation, or rights-based approaches.

International Cooperation Deficit: Despite growing international support for just transitions, especially through initiatives like JETPs, actual grant-based, accessible, and equitable financing remains inadequate for many developing nations.

The Global South Reality

We spoke to experts and other relevant stakeholders spanning across a few countries and regions from the global south, it reveals that while transitions are underway, they are often unjust, underfunded, and misaligned with local priorities:

- Southeast Asia: the region reflects the situation of neglect, extreme vulnerability and underinvestment; and hence exemplifies the just transition challenge. The region’s heavy dependence on coal, which accounted for 9% of global coal production last year, combined with the context of these countries being growing economies with rising emissions creates an urgent need for transition to renewables and energy efficiency. However, research across Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines reveals that while energy transition is happening via large-scale solar projects and rural electrification, it often lacks justice. Countries like Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines are navigating the shift from coal dependency to renewable energy. However, projects often prioritize scale over justice, lacking local participation and long-term sustainability.

- India: As a fast-growing economy committed to net-zero by 2070, India faces complex sectoral transitions that is bound to create structural changes affecting employment, resources, investments, and skill requirements across multiple sectors.

- Automobile industry: Facing large-scale re-skilling and up-skilling requirements; also rising consumption of batteries in EVs leading to transition from lead-acid to lithium-ion batteries demanding change in employment patterns and skill shifts.

- Energy-intensive MSMEs: Such as textiles, brick kilns, and other small enterprises with huge informal workforce and traditional fuel dependencies.

- Coal-Dependent communities: Mining regions face complex socio-economic challenges that go far beyond job losses such as environmental degradation, limited economic diversification, limited social infrastructure (which is also often set up by mining companies’ extended operations), etc. It is because of this, that the communities residing in coal-mining regions need comprehensive support that addresses not only loss of livelihoods, but also skill development, economic diversification, improving public services (like healthcare, education, infrastructure, etc) and building resilient local communities as well as local economies.

The challenge is no longer defining ‘just transition’ but translating research into concrete action, supported by data, community-led models, funding, and sector-specific roadmaps.

- Africa: African perspectives emphasize on the need for locally-led, community-centric actions that avoid new forms of ‘green colonialism’. The vision includes key aspects such as:

- Transitions should be led by African people and for African people

- Focus must be on green industrialization which leverages local resources

- Reliance on financing mechanisms which are non-exploitative and debt-free

- Build skills and capacities to provide surplus energy for global markets while meeting local needs

- Small Island Developing States (SIDS): For SIDS like Sri Lanka, just transition represents nothing less than a systems change. Climate impacts through floods, droughts, and landslides create multifaceted challenges that require comprehensive solutions beyond energy alone, while limited financial resources constrain adaptation and mitigation efforts.

- A developed country’s perspective – Germany: Germany’s experience offers both lessons and cautions for the just transition action by developing nations. The country’s coal phase-out agreement, while comprehensive, had cost a lot in compensation for the affected regions and communities.

The high costs associated with Germany’s model makes it extremely tough for developing nations to replicate similar just transition solution models as they are already facing the challenge of limited and contested fiscal resources vis-a-vis social outcomes, economic growth and decarbonisation.

JETPs – A Reality Check

JETPs were launched with a lot of enthusiasm at COP26 in Glasgow (2021), were touted as a new model for international collaboration and climate finance, aiming to support just and equitable energy transitions. However, early stakeholder feedback highlights deep-rooted structural challenges within this model.

- South African Perspective: While South Africa’s pioneering JETPs marked a symbolic step forward, it has had a limited real-world impact on the energy transition. Experts claimed that the status quo largely persisted, exposing a disconnect between political rhetoric and ground-level change. Key issues included:

- Power Dynamics: Rather than fostering equitable partnerships, JETPs have often maintained traditional donor-recipient dynamics, with embedded conditionalities.

- Financial Transparency: Initial opacity around financial structures led to later revelations that most funding was in the form of loans, not grants, exacerbating debt levels in already fiscally strained nations.

- Inclusivity: Despite being labelled ‘just’, decision-making processes largely excluded civil society, local communities, and other key voices, resulting in minimal participatory engagement.

- Indonesian and Vietnamese Perspectives: Similar observations emerged in both Indonesia and Vietnam. A key concern was the heavy reliance on loan-based financing rather than grant support. Moreover, local civil society organisations were only made aware of partnership details post-announcement, highlighting the ongoing marginalisation of local voices.

Developed Country Perspectives: Representatives from donor nations also shared reflections:

- Missing Nexus between JETPs-Economic Development-Climate Resilience: JETPs tend to focus narrowly on climate objectives without adequately aligning with recipient countries broader economic and resilience priorities, potentially creating policy misalignment.

- Inadequate and unfavorable Financing: Though G7 financial commitments may appear significant, they fall short of actual transition needs and often come with unfavorable terms, raising debt burdens and contravening climate justice principles.

- North-South to South-South Relationships: The traditional North-South dynamic in technology transfer is becoming outdated. With countries like China and India leading advancements in clean technologies, South-South cooperation is emerging as a more relevant model for technological collaboration in the energy transition space.

The Way Forward

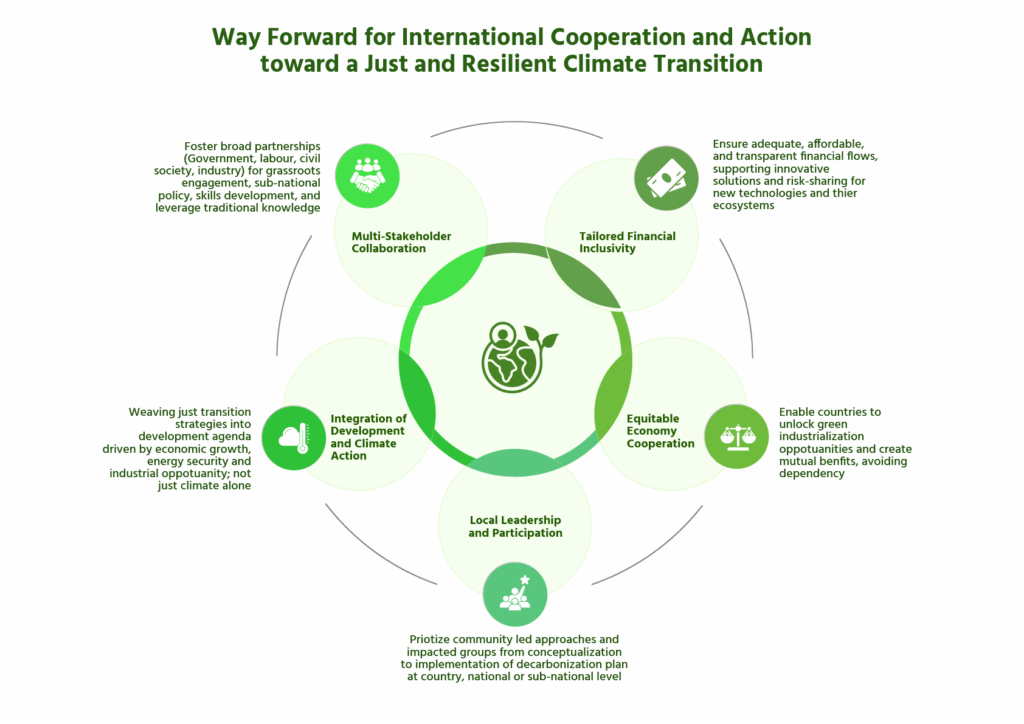

As nations strive to meet climate goals, the focus has shifted beyond the intensity of transition to how it can be achieved in ways that uphold social and economic justice as well as strengthen community resilience. While the concept of JETPs is innovative, there is a risk that they may reproduce longstanding imbalances in power and funding within global climate cooperation. As a way forward, genuine partnerships, prioritizing local leadership, sufficient and accessible financing, alignment with development goals, and meaningful involvement of all affected stakeholders are required. The infographic below describes the key tenets that should be integrated and corrected for all future partnerships from the beginning:

To conclude, the path forward is clear – to amplify local voices and capacities, provide adequate and appropriate financing, implement projects with defined social outcomes and climate urgency, and ensure that those most affected by transition have meaningful influence and decision-making power in shaping their futures as well as implementing actions on the ground. Only in this manner can we move just transitions from rhetoric to reality, from being merely a tell-tale to being a transition strategy.